Indexes are one of the most powerful performance tools in any database—and one of the easiest to misuse. Adding an index can make queries dramatically faster, but adding the wrong index can quietly degrade performance, increase write costs, and complicate maintenance.

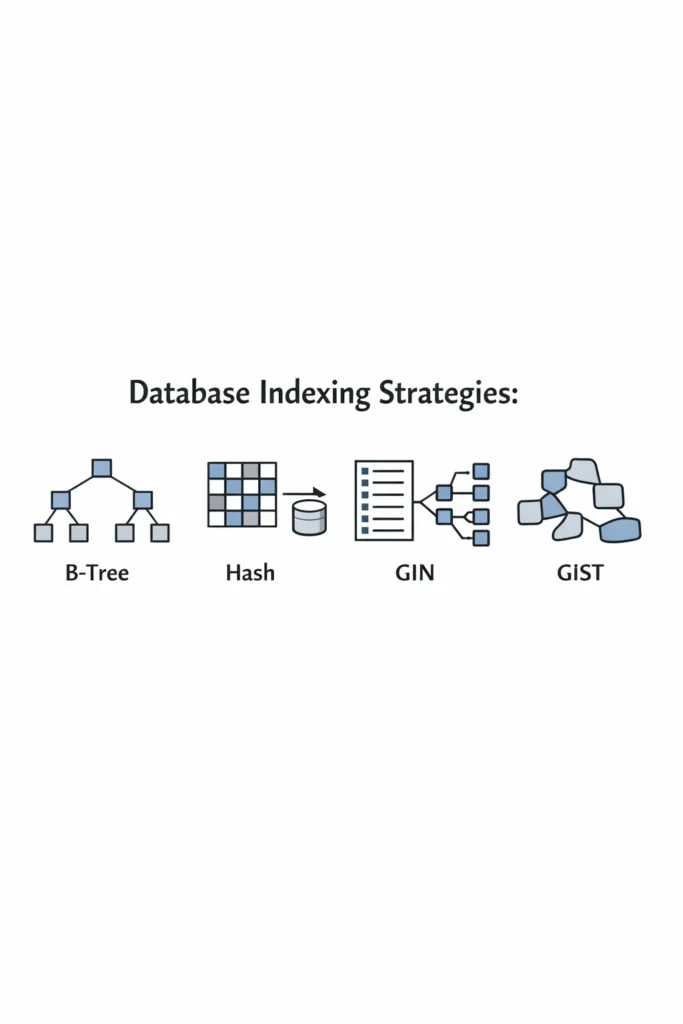

This article explains database indexing strategies with a focus on B-Tree, Hash, GIN, and GiST indexes. The goal is not to memorize definitions, but to understand when each index type makes sense and how to choose deliberately in production systems.

Why Indexing Strategy Matters

Indexes are not free. Every index:

- Consumes memory and disk

- Slows down writes

- Requires maintenance during updates and vacuuming

A good indexing strategy balances read performance with operational cost. Poor strategies often show up as slow writes, bloated indexes, or query plans that ignore indexes entirely.

If you have already explored execution plans and performance analysis, concepts from PostgreSQL performance tuning apply directly here. Indexes only help when the planner can and should use them.

B-Tree Indexes: The Default for a Reason

B-Tree indexes are the most common and versatile index type. They work well for equality comparisons, range queries, sorting, and joins.

When B-Tree Indexes Shine

B-Tree indexes are ideal when:

- Queries use

=or<,>,BETWEEN - Results are ordered with

ORDER BY - Columns are used in joins

- Cardinality is moderate to high

This is why most primary keys and foreign keys are backed by B-Tree indexes.

Common B-Tree Pitfalls

B-Tree indexes lose effectiveness when:

- Columns are wrapped in functions

- Data distribution is extremely skewed

- Too many similar indexes exist

Blindly adding B-Tree indexes to every column often leads to diminishing returns.

Hash Indexes: Narrow but Fast

Hash indexes are optimized for equality comparisons only. They do not support range queries or ordering.

When Hash Indexes Make Sense

Hash indexes can be useful when:

- Queries use strict equality

- No ordering or range filtering is required

- Lookup speed matters more than flexibility

However, their narrow scope limits real-world usefulness.

Why Hash Indexes Are Rarely Used

In practice, B-Tree indexes already handle equality lookups very efficiently. Hash indexes offer limited advantages while introducing constraints.

For most applications, Hash indexes add complexity without meaningful benefit.

GIN Indexes: Searching Inside Data

GIN (Generalized Inverted Index) indexes are designed for multi-valued data. They index individual elements inside a structure rather than the structure as a whole.

Where GIN Indexes Excel

GIN indexes are ideal for:

- JSONB fields

- Arrays

- Full-text search

- Tag-based filtering

If you are working with semi-structured data, patterns discussed in PostgreSQL JSONB best practices often rely on GIN indexes to remain performant.

Trade-offs of GIN Indexes

GIN indexes:

- Consume more memory

- Are slower to update

- Require careful maintenance

They shine in read-heavy workloads but can become expensive under frequent writes.

GiST Indexes: Flexible and Powerful

GiST (Generalized Search Tree) indexes support complex data types and custom search strategies.

Typical GiST Use Cases

GiST indexes are commonly used for:

- Geospatial queries

- Range types

- Similarity searches

- Custom operator classes

They trade some raw performance for flexibility, enabling queries that other index types cannot support efficiently.

GiST vs GIN

While both are generalized index types, they solve different problems.

- Use GIN when searching within composite values

- Use GiST when evaluating relationships between values

Choosing incorrectly often leads to poor query plans.

Choosing the Right Index Type

Index selection should be driven by query patterns, not data types alone.

A practical decision guide:

- Use B-Tree for most columns and joins

- Consider Hash only for strict equality edge cases

- Use GIN for JSONB, arrays, and full-text search

- Use GiST for spatial, range, or similarity queries

This decision-making process mirrors broader architectural trade-offs discussed in database migrations in production, where changes must be intentional and reversible.

Composite and Partial Indexes

Index type alone is not enough. How you define the index matters just as much.

Composite indexes support queries that filter on multiple columns, but column order is critical. Partial indexes reduce size and improve selectivity by indexing only a subset of rows.

These techniques often outperform adding more single-column indexes and should be considered before expanding index count.

Indexes and Write Performance

Every index slows down inserts, updates, and deletes. This cost is cumulative.

High-write systems must be especially careful with:

- GIN indexes on frequently updated fields

- Multiple overlapping indexes

- Indexes on low-selectivity columns

If write latency spikes unexpectedly, indexes are often part of the cause.

Observability: Knowing When Indexes Help

Indexes should be validated, not assumed.

Use execution plans to confirm:

- Index usage

- Row estimates vs actual counts

- Cost vs execution time

Observability practices discussed in monitoring and logging in microservices help surface when indexes stop providing value.

A Realistic Indexing Scenario

Consider a product catalog with relational fields and flexible attributes.

Core filters use B-Tree indexes on product IDs and categories. Dynamic attributes live in JSONB fields backed by GIN indexes. Occasional spatial queries use GiST indexes.

Each index type serves a distinct purpose. None are redundant. Performance remains predictable because indexing strategy reflects access patterns.

Common Indexing Mistakes

Some mistakes appear repeatedly:

- Indexing everything “just in case”

- Ignoring write amplification

- Using the wrong generalized index type

- Never revisiting old indexes

Indexes should evolve with the application, not accumulate indefinitely.

When to Add an Index

Add an index when:

- A query is slow and frequent

- Execution plans show sequential scans

- The column has sufficient selectivity

- Read performance is critical

When to Remove an Index

Remove an index when:

- It is never used

- Write performance suffers

- The query pattern has changed

- Maintenance cost outweighs benefit

Index removal is just as important as index creation.

Conclusion

Database indexing strategies are about alignment. When index types match query patterns, performance improves naturally. When they do not, complexity and cost accumulate quietly.

A practical next step is to audit your indexes. For each one, ask: Which query depends on this? If the answer is unclear, that index is a candidate for review. Intentional indexing scales far better than accidental optimization.

1 Comment