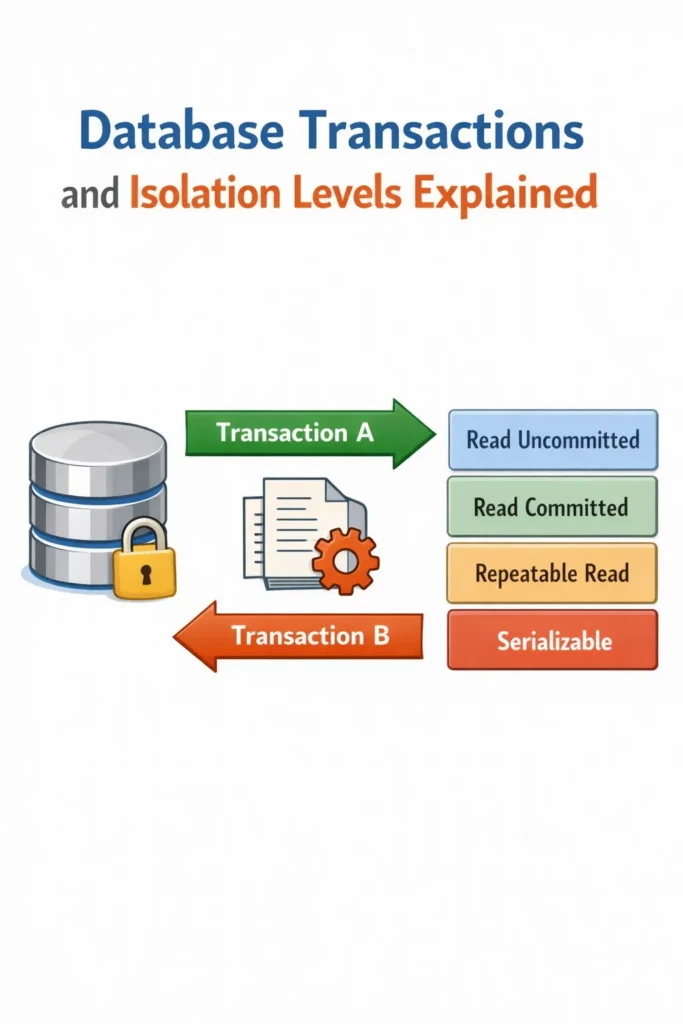

Transactions are the foundation of reliable database systems. Every payment, order, or state change you trust in production depends on them working correctly. Yet many performance bugs, data inconsistencies, and “impossible” edge cases come down to a poor understanding of transaction isolation levels.

This article explains database transactions and isolation levels in a practical, production-focused way. You will learn how transactions work, what isolation levels actually guarantee, and how to choose the right level without sacrificing performance.

What a Database Transaction Really Is

A transaction is a sequence of operations executed as a single unit of work. It either completes entirely or has no effect at all.

Transactions are commonly described using the ACID properties:

- Atomicity – all operations succeed or none do

- Consistency – constraints remain valid

- Isolation – concurrent transactions do not interfere incorrectly

- Durability – committed data survives failures

Isolation is the least intuitive of these and the most frequently misunderstood.

If you already tune queries and indexes, concepts from PostgreSQL Performance Tuning: Indexes, EXPLAIN, and Query Optimization apply here as well—because isolation directly affects query behavior under load.

Why Isolation Levels Exist

Databases process many transactions concurrently. Without isolation rules, transactions could read partial changes, overwrite each other, or observe data in impossible states.

Isolation levels define how much concurrency the database allows and what anomalies are prevented. Higher isolation means stronger guarantees but lower concurrency.

There is no universally “correct” isolation level. The right choice depends on your workload.

Common Concurrency Problems

To understand isolation levels, you must first understand the problems they address.

Dirty Reads

A transaction reads data written by another transaction that has not yet committed. If that transaction rolls back, the read data never actually existed.

Non-Repeatable Reads

A transaction reads the same row twice and gets different values because another transaction committed changes in between.

Phantom Reads

A transaction re-runs a query and sees new rows that were inserted by another transaction after the first read.

These anomalies are not theoretical—they appear regularly in production systems when isolation is misunderstood.

The Standard Isolation Levels

Most relational databases implement four standard isolation levels. Each level prevents more anomalies but reduces concurrency.

Read Uncommitted

This level allows dirty reads. In practice, many databases treat it the same as Read Committed.

It is rarely useful in real applications.

Read Committed

Read Committed prevents dirty reads. A transaction only sees data that has been committed.

However, non-repeatable reads and phantom reads are still possible. This level offers a good balance between safety and performance and is the default in many systems.

Read Committed works well for short-lived transactions and is often sufficient when combined with proper indexing, as discussed in Database Indexing Strategies: B-Tree, Hash, GIN, and GiST.

Repeatable Read

Repeatable Read ensures that once a transaction reads a row, it will always see the same value for that row throughout the transaction.

This prevents non-repeatable reads but may still allow phantom reads depending on the database implementation.

Repeatable Read is useful when consistency within a transaction matters more than raw throughput.

Serializable

Serializable provides the strongest guarantees. Transactions behave as if they ran one after another, even though they may execute concurrently.

This level prevents all concurrency anomalies but introduces:

- Increased locking or conflict detection

- Transaction retries

- Reduced throughput under contention

Serializable isolation is powerful but should be used selectively.

Isolation Levels and Performance

Higher isolation does not automatically mean better correctness for every system.

Long-running transactions under high isolation can:

- Block other transactions

- Increase contention

- Cause retry storms

These issues often appear alongside connection pressure and pool exhaustion, which is why isolation must be considered together with Database Connection Pooling: PgBouncer, HikariCP, and Best Practices.

Isolation and ORMs

Many developers assume their ORM “handles” transactions safely. In reality, ORMs simply pass isolation decisions to the database.

Some ORMs:

- Open transactions implicitly

- Use default isolation without visibility

- Hide retries or failures

Understanding transaction boundaries is essential, especially when using higher-level tools. This is particularly important when working with schema-driven ORMs, as discussed in Prisma ORM: The Complete Guide for Node.js and TypeScript.

Transactions and Migrations

Isolation also matters during schema changes.

Long-running migrations can:

- Hold locks for extended periods

- Block application queries

- Trigger timeouts

Strategies for handling this safely are covered in Database Migrations in Production: Strategies and Tools, where transaction scope and isolation level selection are critical.

Choosing the Right Isolation Level

A practical guideline:

- Use Read Committed for most web applications

- Use Repeatable Read for complex business workflows

- Use Serializable only when correctness absolutely requires it

Always validate assumptions with real workload testing.

Isolation is not a substitute for proper application logic or constraints. It complements them.

Observability: Detecting Isolation Issues

Isolation-related bugs often appear as:

- Inconsistent totals

- Missing or duplicated records

- Rare, hard-to-reproduce errors

Monitoring query latency, lock waits, and transaction retries helps surface these problems early. Observability practices from Monitoring and Logging in Microservices apply directly here.

A Realistic Example

Consider an order-processing system calculating inventory.

Using Read Committed allows fast throughput but risks race conditions if inventory is updated concurrently. Switching to Repeatable Read stabilizes calculations without fully serializing traffic.

Serializable might guarantee correctness, but at the cost of retries during peak traffic.

The correct choice depends on business tolerance for retries versus inconsistencies.

Common Transaction Mistakes

Some mistakes appear repeatedly:

- Running long transactions unnecessarily

- Using Serializable by default

- Ignoring retries at higher isolation

- Assuming ORMs hide isolation complexity

Each of these leads to avoidable production issues.

Conclusion

Database transactions and isolation levels define the balance between correctness and performance. Understanding what each level guarantees—and what it does not—is essential for building reliable systems.

A practical next step is to audit your critical transactions. Identify where isolation matters and where it does not. Making isolation an explicit design choice is one of the most effective ways to prevent subtle data bugs before they reach production.

1 Comment