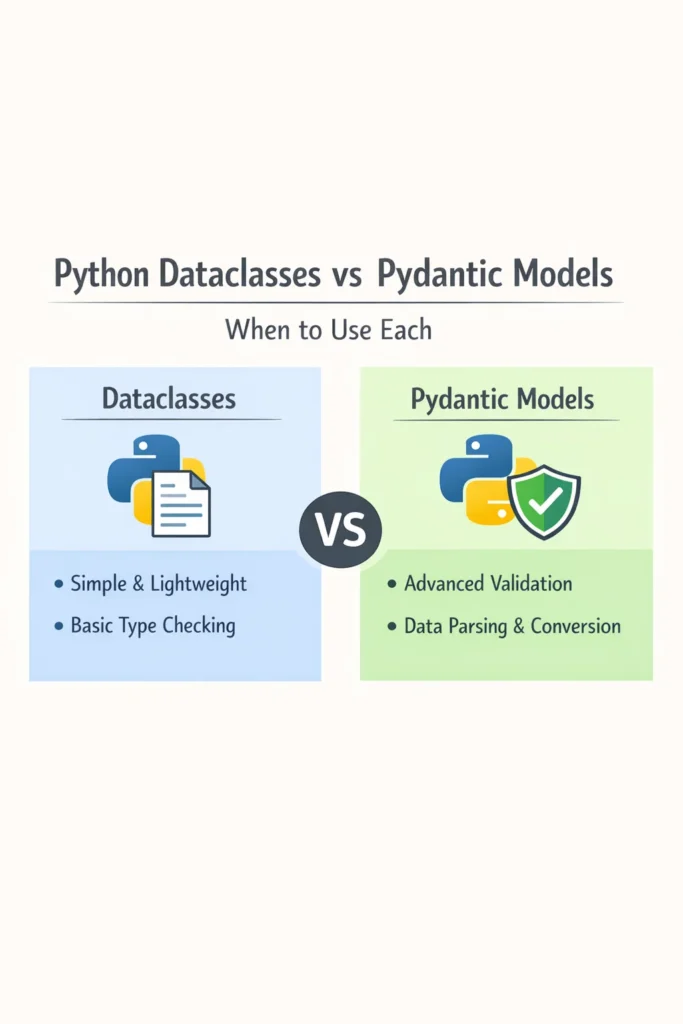

If you write Python and work with structured data, you’ve likely reached the point where you need to choose between dataclasses and Pydantic. Both reduce boilerplate for defining data structures, but they solve fundamentally different problems. Understanding dataclasses vs Pydantic helps you avoid adding unnecessary complexity to internal code or, worse, skipping validation where it actually matters. This guide compares the two approaches with practical examples, performance considerations, and a clear decision framework so you can pick the right tool for each situation.

What Are Python Dataclasses?

Python dataclasses are a decorator-based feature in the standard library, available since Python 3.7. They automatically generate __init__, __repr__, __eq__, and other dunder methods based on class-level type annotations. However, dataclasses do not perform any runtime validation — the type annotations are hints for developers and static type checkers, not enforcement rules.

from dataclasses import dataclass

@dataclass

class User:

name: str

email: str

age: int

active: bool = True

This generates a constructor, a readable string representation, and equality checks automatically. Because dataclasses are part of the standard library, they add zero dependencies to your project. For more on how type hints work in Python, see our guide on Python type hints and mypy.

What Is Pydantic?

Pydantic is a third-party library that provides runtime data validation and serialization using Python type annotations. When you create a Pydantic model instance, it validates every field against its type and raises a detailed error if the data doesn’t match. Additionally, Pydantic v2 is rebuilt on a Rust core, which makes validation significantly faster than the pure-Python v1.

from pydantic import BaseModel, EmailStr

class User(BaseModel):

name: str

email: EmailStr

age: int

active: bool = True

The key difference is visible at instantiation. Creating User(name="Alice", email="not-an-email", age=25) raises a ValidationError with Pydantic, while the equivalent dataclass would accept the invalid email without complaint. Pydantic also coerces types when possible — passing age="25" as a string automatically converts it to the integer 25.

Dataclasses vs Pydantic: Key Differences

This comparison covers Pydantic v2 and Python 3.10+ dataclasses, which represent the current state of both tools.

| Feature | Dataclasses | Pydantic v2 |

|---|---|---|

| Runtime validation | No (type hints only) | Yes (automatic) |

| Type coercion | No | Yes (configurable) |

| JSON serialization | Manual (asdict + json.dumps) | Built-in (.model_dump_json()) |

| JSON deserialization | Not supported | Built-in (.model_validate_json()) |

| Custom validators | Manual in __post_init__ | Decorators (@field_validator) |

| Dependencies | None (stdlib) | pydantic package |

| Instantiation speed | Faster (no validation) | Slower (validates all fields) |

| Nested model support | Basic | Full with recursive validation |

| OpenAPI/JSON Schema | Not supported | Built-in (.model_json_schema()) |

| Immutability | frozen=True | model_config = ConfigDict(frozen=True) |

Syntax and Basic Usage Compared

Both tools use type annotations to define fields, but the patterns diverge as requirements grow. Here’s how common operations look side by side.

Defining a Simple Model

# Dataclass approach

from dataclasses import dataclass, field

@dataclass

class Product:

name: str

price: float

tags: list[str] = field(default_factory=list)

# Pydantic approach

from pydantic import BaseModel

class Product(BaseModel):

name: str

price: float

tags: list[str] = []

For simple structures, the syntax is nearly identical. Pydantic handles mutable default values automatically, while dataclasses require field(default_factory=list) to avoid the shared mutable default trap. This small convenience adds up across a large codebase.

Adding Validation Logic

# Dataclass with manual validation

from dataclasses import dataclass

@dataclass

class Product:

name: str

price: float

def __post_init__(self) -> None:

if self.price < 0:

raise ValueError("Price cannot be negative")

if not self.name.strip():

raise ValueError("Name cannot be empty")

# Pydantic with declarative validators

from pydantic import BaseModel, field_validator

class Product(BaseModel):

name: str

price: float

@field_validator("price")

@classmethod

def price_must_be_positive(cls, v: float) -> float:

if v < 0:

raise ValueError("Price cannot be negative")

return v

@field_validator("name")

@classmethod

def name_must_not_be_empty(cls, v: str) -> str:

if not v.strip():

raise ValueError("Name cannot be empty")

return v

The dataclass approach uses __post_init__ for all validation, which means every check lives in a single method. Pydantic’s field validators are more granular — each validator targets a specific field and runs independently. For two or three checks, the difference is minor. However, when a model has ten validated fields, Pydantic’s per-field approach stays organized while __post_init__ becomes a wall of if-statements. For more on Python decorator patterns used by both approaches, see our Python decorators guide.

Serialization and Deserialization

Serialization is where the gap between dataclasses and Pydantic becomes most apparent. Converting data to and from JSON, dictionaries, or API responses is a core requirement for web applications.

# Dataclass serialization — manual

import json

from dataclasses import dataclass, asdict

@dataclass

class User:

name: str

email: str

age: int

user = User(name="Alice", email="alice@example.com", age=30)

# To dict

user_dict = asdict(user)

# To JSON

user_json = json.dumps(asdict(user))

# From dict — no built-in method

user_from_dict = User(**some_dict)

# From JSON — manual parsing

user_from_json = User(**json.loads(some_json_string))

# Pydantic serialization — built-in

from pydantic import BaseModel

class User(BaseModel):

name: str

email: str

age: int

user = User(name="Alice", email="alice@example.com", age=30)

# To dict (with options to include/exclude fields)

user_dict = user.model_dump()

user_dict_without_email = user.model_dump(exclude={"email"})

# To JSON (serialized directly, no intermediate dict)

user_json = user.model_dump_json()

# From dict — with validation

user_from_dict = User.model_validate(some_dict)

# From JSON — parsed and validated in one step

user_from_json = User.model_validate_json(some_json_string)

Pydantic’s serialization is both more convenient and more powerful. The model_dump method supports include, exclude, by_alias, and exclude_none parameters that cover most API response formatting needs without writing custom logic. Furthermore, model_validate_json parses JSON and validates the data in a single pass through the Rust core, which is faster than json.loads followed by manual construction.

For web frameworks that depend on this serialization pipeline, Pydantic is essentially mandatory. FastAPI, for instance, uses Pydantic models for both request parsing and response serialization — see our FastAPI REST API guide for how this works in practice.

Performance Considerations

Performance differences between dataclasses and Pydantic matter primarily in hot paths where you create thousands of instances per second.

Dataclass instantiation is faster because there’s no validation step. Creating a dataclass instance is essentially a regular __init__ call with attribute assignment. Pydantic v2, while significantly faster than v1 thanks to its Rust core, still validates every field on instantiation.

For most web applications, the difference is negligible. A typical API endpoint creates a handful of model instances per request, and the database query or network call dominates the response time. However, in data processing pipelines that create millions of objects in tight loops, the overhead adds up.

A practical guideline: if you’re processing bulk data and validation already happened at the boundary (for example, data read from a trusted internal database), dataclasses avoid repeated validation of already-clean data. If you’re accepting external input, the validation cost is justified because the alternative — writing manual validation logic — is both slower to develop and more error-prone.

Nested Models and Complex Structures

Both tools support nested data structures, but Pydantic handles them with deeper integration.

# Pydantic nested models with recursive validation

from pydantic import BaseModel

class Address(BaseModel):

street: str

city: str

zip_code: str

class Company(BaseModel):

name: str

address: Address

# Pydantic validates the nested Address automatically

company = Company.model_validate({

"name": "Acme Corp",

"address": {

"street": "123 Main St",

"city": "Springfield",

"zip_code": "62701",

},

})

With dataclasses, nested dict-to-object conversion requires manual handling. The User(**some_dict) pattern works for flat structures, but a nested dictionary won’t automatically become a nested dataclass instance. Libraries like dacite or cattrs fill this gap, but they’re additional dependencies that bring you closer to what Pydantic provides out of the box.

Real-World Scenario: Choosing the Right Tool in a FastAPI Project

Consider a mid-sized FastAPI application with 20-25 endpoints that serves as the backend for a project management tool. The small development team initially uses Pydantic models everywhere — for API request bodies, response schemas, database row mappings, and internal service-layer data transfer objects.

As the codebase grows, the team notices that internal service functions pass Pydantic models between layers even when no validation or serialization is needed. A function that calculates task priority takes a Pydantic TaskData model, validates all 12 fields on instantiation, and then only reads two of them. Multiply this across dozens of internal function calls per request, and the unnecessary validation adds measurable latency under load.

The team adopts a practical boundary: Pydantic models at the API edges (request parsing, response serialization, external API clients) and dataclasses for internal data structures passed between services. The API layer validates incoming data with Pydantic, converts to internal dataclass representations, and converts back to Pydantic response models on the way out. This approach keeps validation where it matters and reduces overhead in internal processing.

The key trade-off is maintaining two parallel model definitions for some entities — a Pydantic model for the API layer and a dataclass for the service layer. For the team’s scale, this is manageable and the performance improvement under concurrent load justifies the duplication. However, for a smaller API with fewer internal processing steps, using Pydantic everywhere is simpler and the performance difference is unnoticeable. For a deeper look at Pydantic validation patterns in FastAPI, see our advanced Pydantic validation guide.

When to Use Dataclasses

- You need lightweight data containers for internal application logic where runtime validation adds no value

- Your data comes from a trusted source like an internal database or a validated upstream service

- You want zero external dependencies for a library or package that others will install

- Performance is critical and you’re creating thousands of instances in tight loops with already-validated data

- You’re defining simple configuration objects, enums, or value types that don’t cross system boundaries

When NOT to Use Dataclasses

- You’re parsing data from external sources like API requests, user input, webhooks, or third-party APIs where the shape and types are not guaranteed

- You need built-in JSON serialization with field inclusion/exclusion, aliasing, or custom encoders

- You want automatic OpenAPI or JSON Schema generation for API documentation

- Your models have complex validation rules that would make

__post_init__unwieldy

When to Use Pydantic

- You’re building an API and need request validation, response serialization, and OpenAPI docs from the same model definition

- Your application processes data from untrusted or external sources that require validation at the boundary

- You need type coercion (for example, accepting

"true"as a boolean or"123"as an integer from query parameters) - You want a rich ecosystem of field types like

EmailStr,HttpUrl,SecretStr, and integration with frameworks like FastAPI or LangChain - You need settings management with environment variable parsing via

pydantic-settings

When NOT to Use Pydantic

- You’re defining internal data structures that never touch system boundaries and don’t need validation

- You’re building a library that should minimize dependencies for its users

- Your hot path creates millions of objects from already-validated data and the validation overhead is measurable

- The model is a simple data carrier with no validation, serialization, or schema generation requirements — dataclasses do this with less machinery

Common Mistakes with Dataclasses and Pydantic

- Using Pydantic everywhere by default. Pydantic is powerful, but using it for every data structure in your application adds validation overhead where it isn’t needed. Reserve Pydantic for system boundaries and use dataclasses or plain classes internally.

- Assuming dataclass type hints enforce types at runtime. A dataclass with

age: intwill happily acceptage="not a number"without raising an error. The annotation is for documentation and static analysis only. If you need runtime enforcement, you must add manual checks in__post_init__or use Pydantic instead. - Ignoring Pydantic’s strict mode. By default, Pydantic coerces types (for example,

"123"becomes123). While convenient for API parsing, this can mask bugs in internal code. Usemodel_config = ConfigDict(strict=True)when you want exact type matching without coercion. - Using

asdictin performance-critical paths. Thedataclasses.asdictfunction recursively copies the entire structure, which is slow for deeply nested objects. If you only need a flat dict or specific fields, access attributes directly instead of converting the whole object. - Not leveraging Pydantic’s

model_configfor shared settings. Settings likefrozen=True,str_strip_whitespace=True, orvalidate_default=Trueapply to the entire model and prevent repetitive per-field configuration. Teams often write per-field validators for behavior that a single config option handles. - Mixing the two without a clear boundary. The worst outcome is a codebase where some functions accept dataclasses and others accept Pydantic models for the same data, with conversion happening ad hoc. Define a clear layer — typically the API boundary — where Pydantic models convert to and from internal dataclasses.

Conclusion

The choice between dataclasses vs Pydantic comes down to one question: does this data need runtime validation? At system boundaries where external data enters your application, Pydantic’s automatic validation, type coercion, and serialization eliminate an entire class of bugs. For internal data structures passed between trusted layers, dataclasses provide the same structured representation without the validation overhead.

In practice, most Python web applications benefit from using both — Pydantic at the edges and dataclasses inside. Start with Pydantic for your API models, and reach for dataclasses when you find yourself creating validated objects from data that was already validated upstream. For your next step, explore our Flask vs FastAPI vs Django comparison to see how these data modeling choices fit into the broader Python framework landscape.