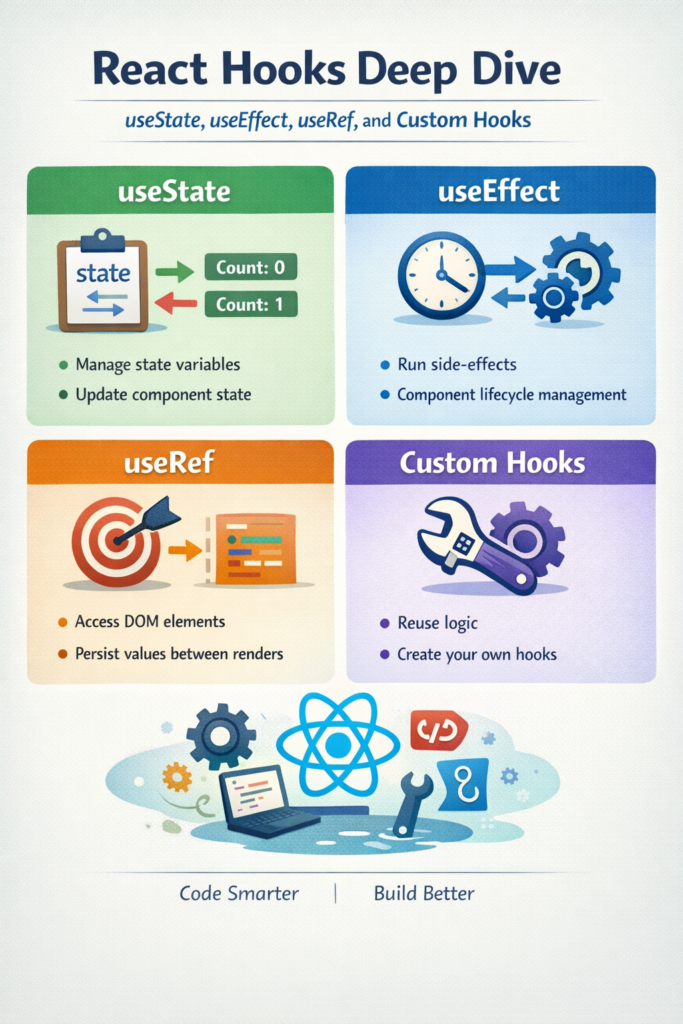

If you are building modern React applications, hooks are unavoidable. However, many real-world bugs and performance issues come from misunderstanding how hooks behave across renders. This react hooks deep dive is written for developers who already use hooks but want a stronger mental model to avoid stale state, effect loops, and brittle abstractions.

By the end of this article, you will understand how useState, useEffect, and useRef actually work, how to design custom hooks that scale, and where these patterns break down in production codebases.

Understanding the Mental Model Behind React Hooks

Hooks are not general-purpose utilities. They are tightly coupled to React’s render cycle and reconciliation process. Each hook call is associated with a specific position in the render order, which is why hooks must always be called at the top level and never conditionally.

This becomes easier to reason about once you understand how React schedules renders and updates components, something that also becomes very clear when building a React app with Next.js 14 in real-world scenarios.

React’s core behavior around hooks, renders, and effects is documented in the official React Hooks reference, which is worth revisiting whenever effects start behaving unexpectedly.

useState: Local State That Triggers Renders

useState stores a value that persists across renders and triggers a re-render when updated.

import { useState } from 'react';

function Counter() {

const [count, setCount] = useState(0);

function increment() {

setCount(prev => prev + 1);

}

return <button onClick={increment}>Count: {count}</button>;

}

Two details are critical in production. First, state updates are scheduled, not applied immediately. Second, the functional updater form prevents stale state bugs when multiple updates are batched together.

These behaviors are explained in depth in the official useState documentation and should be treated as the source of truth.

Common useState Pitfalls

A frequent mistake is storing derived data in state, such as filtered lists or computed totals. This often leads to synchronization issues where state becomes duplicated and difficult to reason about. In practice, derived values should be calculated during render or memoized only when performance profiling justifies it.

As applications grow, local state decisions often turn into architectural concerns. Many of the same trade-offs discussed in react native state management comparison apply here as well, especially when deciding what truly belongs in component state.

Another common issue is using useState for values that do not affect rendering, such as timers or mutable instance data. In those cases, useRef is usually the correct tool.

useEffect: Synchronizing With the Outside World

useEffect exists to synchronize your component with external systems such as APIs, subscriptions, timers, or browser APIs. It is not intended as a general lifecycle replacement, even though it may resemble one at first glance.

import { useEffect, useState } from 'react';

function UserProfile({ userId }) {

const [user, setUser] = useState(null);

useEffect(() => {

const controller = new AbortController();

async function loadUser() {

const response = await fetch(`/api/users/${userId}`, {

signal: controller.signal,

});

if (!response.ok) {

throw new Error(`HTTP ${response.status}`);

}

const data = await response.json();

setUser(data);

}

loadUser().catch(error => {

if (error.name !== 'AbortError') {

console.error('Failed to load user', error);

}

});

return () => controller.abort();

}, [userId]);

if (!user) return null;

return <div>{user.name}</div>;

}

This pattern avoids a common production issue where state updates occur after a component unmounts or after input props change mid-request. The reasoning behind effect timing, dependencies, and cleanup is explained clearly in the official useEffect reference.

Why Dependency Arrays Cause Real Bugs

The dependency array controls when an effect runs, not what it logically depends on. If dependencies are incorrect, you typically see one of two failure modes: stale closures or infinite re-runs.

In practice, repeatedly fighting the dependency array is a strong signal that the effect is doing too much. Extracting logic into a custom hook often reduces complexity and makes dependencies explicit.

These problems often surface as performance issues, closely related to the topics discussed in debouncing, throttling, and performance optimisations.

Real-World Scenario: Effect Loops After a Refactor

In a mid-sized React application with roughly 20–30 screens and a small team, effect loops commonly appear after refactors that attempt to centralize data fetching. Inline functions or object literals are added to dependency arrays, unintentionally changing on every render.

The trade-off is convenience versus stability. The practical fix is to move unstable logic out of the render path or into a custom hook with a clearly defined responsibility.

Async logic inside effects also benefits from the same principles described in the JavaScript async/await guide, particularly around error handling and cancellation.

useRef: Mutable Values Without Re-Renders

useRef provides a stable, mutable container that persists across renders without triggering re-renders when updated.

import { useRef, useEffect } from 'react';

function AutoFocusInput() {

const inputRef = useRef(null);

useEffect(() => {

inputRef.current?.focus();

}, []);

return <input ref={inputRef} />;

}

While DOM access is the most visible use case, refs are equally useful for storing timers, previous values, or instance-like data.

function usePrevious(value) {

const ref = useRef();

useEffect(() => {

ref.current = value;

}, [value]);

return ref.current;

}

Because refs do not trigger re-renders, they should never be used to store values that affect what is displayed on screen. Doing so leads to inconsistent UI behavior that is difficult to debug.

Custom Hooks: Reusable Logic Without Abstraction Leakage

Custom hooks allow you to extract reusable logic without introducing inheritance or higher-order components. Any time you see duplicated hook logic across components, a custom hook is usually the correct solution.

import { useEffect, useState } from 'react';

function useWindowSize() {

const [size, setSize] = useState({

width: window.innerWidth,

height: window.innerHeight,

});

useEffect(() => {

function handleResize() {

setSize({

width: window.innerWidth,

height: window.innerHeight,

});

}

window.addEventListener('resize', handleResize);

return () => window.removeEventListener('resize', handleResize);

}, []);

return size;

}

Well-designed custom hooks focus on a single responsibility, expose a minimal API, and hide internal implementation details. Many effective hooks rely on composition patterns similar to those explored in functional programming techniques in JavaScript.

From a testing perspective, hooks structured this way are significantly easier to validate, especially when combined with approaches described in unit testing with Jest and Vitest in modern JS projects.

When to Use React Hooks Deep Dive Concepts

- When building function-based React components

- When refactoring class components into hooks

- When debugging stale state or effect-related bugs

- When extracting reusable logic into custom hooks

When NOT to Use React Hooks Deep Dive Patterns

- When simple inline logic is clearer

- When hooks obscure readability rather than improve it

- When state belongs in a global store or server cache

- When effects are used to control rendering instead of synchronization

Common Mistakes

- Using

useEffectfor derived state - Ignoring dependency arrays

- Storing UI-driven values in refs

- Creating overly generic custom hooks

- Treating hooks as lifecycle replacements

Conclusion and Next Steps

Hooks enforce discipline by design. useState manages render-driven state, useEffect synchronizes external systems, useRef stores mutable values, and custom hooks enable reuse without inheritance. Understanding these boundaries is what separates maintainable React applications from fragile ones.

As a next step, audit one complex component in your codebase and verify that each hook is solving the correct problem. That single exercise often reveals architectural issues worth fixing before they scale.

1 Comment