Introduction

Distributed systems power modern applications, from social networks handling billions of users to financial platforms processing millions of transactions. Building reliable distributed systems requires understanding the fundamental constraints that govern their behavior. The CAP theorem, proposed by Eric Brewer in 2000 and formally proven by Gilbert and Lynch in 2002, defines these constraints precisely. It states that during a network partition, a distributed system must choose between consistency and availability. This guide explains the CAP theorem in depth, explores how modern databases handle these trade-offs, and provides practical guidance for making informed architectural decisions.

What Is the CAP Theorem

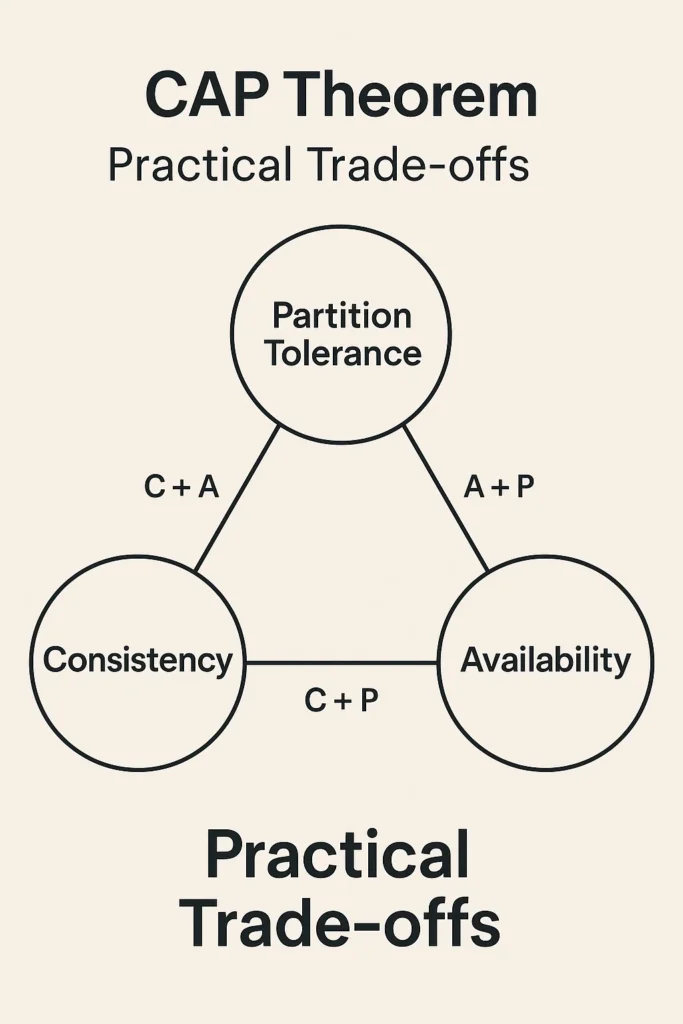

The CAP theorem states that a distributed data store can provide at most two of three guarantees simultaneously when a network partition occurs:

- Consistency (C) – Every read receives the most recent write or an error. All nodes see the same data at the same time.

- Availability (A) – Every request receives a non-error response, though the data may not be the most recent.

- Partition Tolerance (P) – The system continues operating despite network failures that prevent some nodes from communicating with others.

The theorem often gets misunderstood as requiring you to permanently choose two properties. In reality, the choice only matters during partitions. When the network functions normally, systems can provide all three properties. The CAP theorem describes behavior under failure conditions, not normal operations.

Understanding Each Property

Consistency

Consistency in CAP refers to linearizability, a strong consistency model where operations appear to occur instantaneously at some point between their start and end times. When a write completes, all subsequent reads must return that value or a later one.

Consider a banking application where a user transfers money between accounts. Strong consistency ensures that checking the balance immediately after the transfer shows the updated amount, regardless of which database node handles the request.

Achieving consistency requires coordination between nodes. Before confirming a write, the system must ensure enough nodes have recorded the change. This coordination introduces latency and creates vulnerability to network issues. If nodes cannot communicate to agree on the current state, the system must either return potentially stale data or reject the request.

Availability

Availability means every request to a non-failing node eventually receives a response. The system remains operational and responsive, even if some nodes fail or become unreachable.

High availability prioritizes responding to users over data accuracy. An available system might return outdated data during a partition rather than returning an error or timing out. For many applications, showing slightly stale data is preferable to showing nothing at all.

Social media feeds exemplify availability prioritization. Users expect the feed to load quickly. If some posts appear slightly delayed or out of order, the impact is minimal compared to the frustration of a loading spinner or error message.

Partition Tolerance

Network partitions occur when communication breaks down between groups of nodes. This can happen due to network hardware failures, configuration errors, or even software bugs. In distributed systems spanning multiple data centers or cloud regions, partitions are not theoretical concerns but regular occurrences.

Partition tolerance means the system continues functioning despite these communication failures. Since network partitions cannot be prevented entirely, any distributed system that spans multiple nodes must be partition tolerant. This is why the practical choice is between CP (consistency during partitions) and AP (availability during partitions).

CAP Trade-off Categories

CP Systems

CP systems prioritize consistency over availability during partitions. When nodes cannot communicate, the system refuses requests rather than risk returning inconsistent data.

Examples:

- MongoDB (with majority write concern) – Requires acknowledgment from a majority of replicas before confirming writes

- HBase – Built on Hadoop, provides strong consistency for large-scale data

- etcd – Uses Raft consensus for distributed key-value storage

- Zookeeper – Coordination service that maintains strict ordering guarantees

CP systems suit applications where correctness outweighs responsiveness. Financial transactions, inventory management, and coordination services typically require CP guarantees to prevent issues like double-spending or overselling.

AP Systems

AP systems prioritize availability over consistency during partitions. They continue serving requests even when some nodes are unreachable, accepting that different nodes may temporarily have different data.

Examples:

- Cassandra – Highly available with tunable consistency levels

- DynamoDB – AWS managed database with eventual consistency by default

- CouchDB – Document database with multi-master replication

- Riak – Distributed key-value store with high availability

AP systems employ eventual consistency, meaning updates propagate to all nodes over time. After a partition heals, conflict resolution mechanisms reconcile divergent data. Common strategies include last-write-wins, vector clocks, and application-specific merge functions.

CA Systems

CA systems theoretically provide consistency and availability but cannot tolerate partitions. In practice, this means single-node systems or tightly coupled clusters that fail entirely when any network issue occurs.

Examples:

- Single-node PostgreSQL – No partition concerns with one node

- Single-node MySQL – Consistent and available until the node fails

CA systems rarely exist in production distributed deployments because network partitions are inevitable at scale. When systems claim CA properties, they typically either cannot scale horizontally or silently sacrifice one property during partitions.

Beyond Binary Choices

Modern databases often provide tunable consistency, allowing different operations to make different trade-offs.

Cassandra Tunable Consistency

Cassandra lets you specify consistency levels per query:

- ONE – Fastest, read from any single replica

- QUORUM – Read from majority of replicas, balances speed and consistency

- ALL – Read from all replicas, strongest consistency, lowest availability

This flexibility allows optimizing different operations based on their requirements within the same database.

MongoDB Write Concerns

MongoDB offers configurable write acknowledgment:

- w: 1 – Acknowledge after primary node writes

- w: majority – Acknowledge after majority of replicas write

- w: 0 – Fire and forget, maximum speed

CockroachDB Serializable Isolation

CockroachDB attempts to provide strong consistency across distributed nodes using a combination of hybrid logical clocks and Raft consensus. It prioritizes consistency while maintaining reasonable availability through automatic failover and multi-region deployments.

Practical Decision Framework

When designing systems, consider these questions:

What Happens If Users See Stale Data?

If showing outdated information causes significant problems (financial loss, safety issues, legal compliance), prioritize consistency. If users can tolerate temporarily stale data (social feeds, product catalogs, analytics), availability may be more important.

What Happens If the System Is Unavailable?

If downtime directly impacts revenue or user safety, availability is critical. E-commerce sites lose sales during outages. Healthcare systems must remain accessible. Consider the cost of unavailability versus the cost of inconsistency.

How Often Do Partitions Occur?

Single data center deployments experience fewer partitions than globally distributed systems. The frequency and duration of expected partitions should influence your trade-off decisions.

Can You Use Different Strategies for Different Data?

Many applications benefit from polyglot persistence, using different databases for different data types. User authentication might use a CP database while activity feeds use an AP database.

Real-World Examples

Banking and Financial Systems

Banks typically prioritize consistency. Account balances must be accurate to prevent overdrafts, double-spending, and regulatory violations. Systems may become temporarily unavailable during network issues rather than risk incorrect balances.

Social Media Platforms

Social networks prioritize availability. Users expect feeds to load instantly. If some posts appear slightly delayed or a like count is momentarily outdated, the impact is minimal. Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram use AP architectures with eventual consistency.

E-Commerce Inventory

Product catalogs can tolerate eventual consistency, but inventory counts often need stronger guarantees. Overselling products creates customer service issues and fulfillment problems. Many e-commerce systems use hybrid approaches with AP for catalog data and CP for inventory.

DNS Systems

DNS prioritizes availability with eventual consistency. DNS records propagate gradually across servers worldwide. Users may see different IP addresses during updates, but the system remains available. This trade-off is acceptable because temporary inconsistency rarely causes serious problems.

Testing and Validation

Understanding theoretical trade-offs is essential, but testing validates actual system behavior:

- Jepsen testing – Industry-standard tool for testing distributed systems under partition conditions

- Chaos engineering – Deliberately inject failures to verify system resilience

- Network partition simulation – Use tools like tc (traffic control) to simulate network issues

- Load testing during failures – Verify behavior under realistic partition scenarios

Conclusion

The CAP theorem is not a limitation to overcome but a fundamental constraint that guides architectural decisions. Understanding these trade-offs helps you choose appropriate databases and design resilient systems. During normal operations, modern databases can often provide all three properties. The critical decisions concern behavior during partitions, which inevitably occur in distributed systems. By analyzing your application requirements, understanding the costs of inconsistency versus unavailability, and testing actual system behavior, you can make informed decisions that balance performance, reliability, and user experience.

For implementing resilience patterns in your applications, read Circuit Breakers and Resilience Patterns in Microservices. To explore event-driven architectures, see Event-Driven Microservices with Kafka. For API comparison considerations, check out REST vs GraphQL vs gRPC. You can also explore the Google Cloud Architecture Center for additional distributed systems guidance.

1 Comment